Support vital abortion stigma busting efforts today!

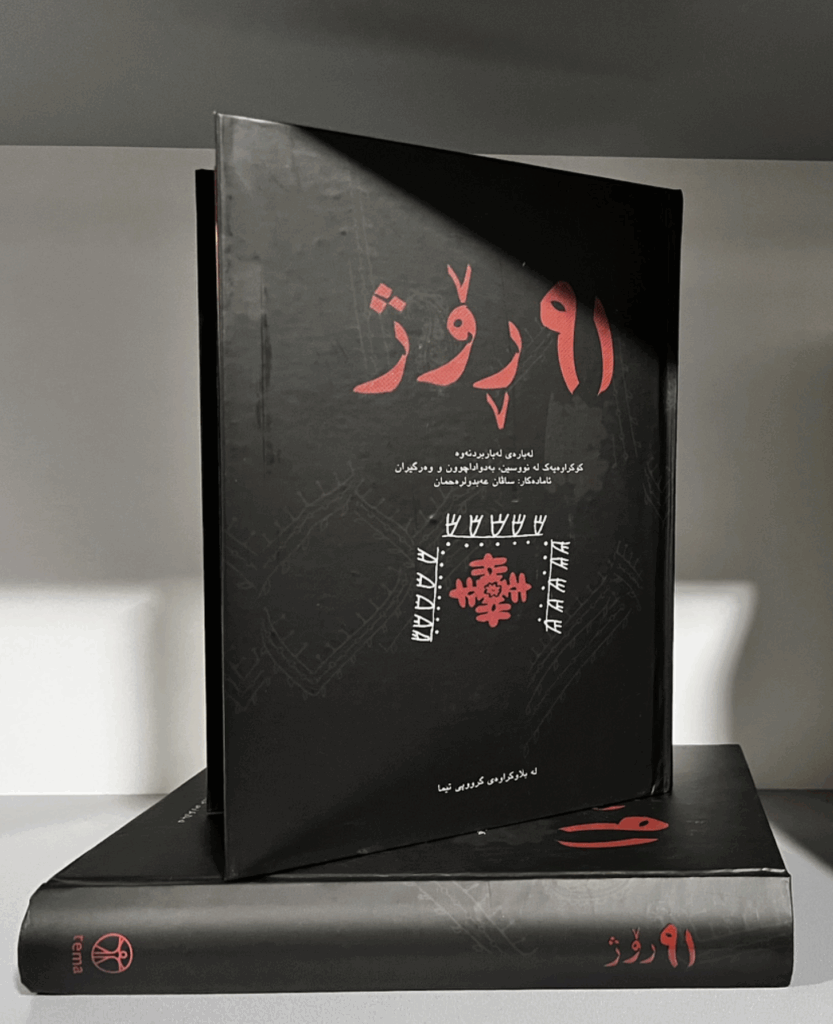

DONATE91 Days: The Book Challenging Abortion Stigma in Kurdistan

Posted November 5, 2025 by the inroads teamIn the Kurdistan Region of Iraq, abortion is permitted only when the pregnant person’s life is in danger — and even then, it requires authorization from both health professionals and the husband. Across Iraq, abortion remains largely criminalized, forcing many to face stigma, silence, and unsafe conditions when navigating reproductive care.

Amid this reality, inroads member Savan Abdulrahman – a Kurdish researcher, writer, and founder of the Tema group – produced an transformative book. Released in 2024, 91 Days is the first book written in Kurdish to explore abortion in depth, weaving together history, politics, philosophy, medicine, psychology, and law with lived experiences and artistic reflection. Through its 14 chapters, the book opens space for conversations long considered taboo, challenging stigmatized narratives and reclaiming knowledge and language.

We spoke with Savan about what inspired her to write 91 Days, how stigma intersects with broader systems of oppression in Kurdistan, and why it was essential to publish this work. Read below for her reflections and insights on freedom, language, and collective courage. 💚

What motivated you to write this book, and what stigmatizing narratives or taboos were you hoping to challenge?

SAVAN: The importance of researching such a sensitive topic stems from years of youth activism and group discussions around crucial issues like freedom, politics, and social structures. By reflecting on the concerns and gaps within our society—particularly among youth—we’ve come to recognize that freedom of choice is a fundamental need for every individual. Humans thrive on a sense of freedom: the freedom of speech, freedom of expression, the freedom to wear certain clothes, to walk under the starlit sky at night, and so on. For me, the idea of freedom of choice over one’s own body emerged as the umbrella under which the broader definition of freedom can be understood. This realization became the starting point for addressing this particular topic in my home country.

In your research, how have you seen abortion stigma intersect with broader systems of oppression in Kurdistan?

SAVAN: Throughout my years of research and engagement with stakeholders, professionals in law, health, and NGOs, as well as individuals from my community, I have come to understand that abortion stigma plays a major role in reinforcing and redirecting inequalities and oppression against women. From a patriarchal perspective, a woman is often seen as needing her husband’s approval for any kind of decision-making. A woman who has experienced rape does not have the free will to access a safe abortion or proper healthcare. A child born from rape is often treated as an outsider within their community.

Many women also lack access to knowledge that would allow them to protect their health and make informed decisions. The stigma surrounding abortion prevents open discussions and sharing of experiences, creating a culture of silence where the community collectively feels the pain, yet suffers it quietly.

Through intensive and detailed conversations on this topic, we came to understand that even if legal reforms were to support women’s basic needs for early-stage abortion, the community’s reaction would likely remain hostile. This strong social stigma continues to influence the judiciary system and push progress backward.

The best alternative we identified is continuous awareness-raising and open, consistent conversations about the issue, in line with broader advocacy efforts, as the most effective way to move the cause forward.

Could you share examples of how communities have resisted or navigated barriers to access abortion care and stigma in Kurdistan?

SAVAN: To answer this question, I would hypothetically divide my community into two categories. The first category includes people who do not hold strong prejudgments and are open to discussion about new ideas and topics. Many of them are defenders of human rights and empathetic toward any form of oppression. This group also includes people who recognize that they “don’t know” — meaning they are willing to learn and listen before forming opinions. In my years of research, I have been fortunate to encounter more individuals from this category, who often engaged in progressive dialogues and contributed to the conversations for my book.

The second category consists of individuals with strong religious backgrounds — mostly religious leaders and their followers — who tend to oppose any kind of progress without engaging in open conversation. They often become barriers to broader community discussions.

One example that clearly illustrates this divide occurred during a focus group discussion on access to abortion. One participant became angry, claiming that discussing this topic would encourage women to engage in sexual activity, which he considered forbidden. Unfortunately, due to this tension, we had to cancel the discussion for the participants’ safety. However, this incident became a valuable insight for our research, revealing that for many within this second group, the deeper fear is not just about abortion itself, but about women gaining autonomy over their own bodies.

What cultural, policy, or community-level shifts do you think are most urgently needed currently to advance reproductive justice in Kurdistan?

SAVAN: I believe that, at this stage in Kurdistan, active efforts toward awareness-raising and the creation of safe spaces for youth to express themselves and engage in open dialogue are crucial on a cultural level.

On the policy level, it is essential to establish frameworks that allow women to make decisions about their own bodies and to have safe options for unwanted pregnancies at very early stages. Achieving this requires collaboration among activists, lawyers, doctors, sociologists, and professionals from various sectors — especially the educational sector — to collectively advocate for change.

Most importantly, Kurdistan needs local solutions that can bridge the gap between opposing perspectives and find a middle ground that respects both cultural sensitivities and women’s fundamental rights.

How can solidarity efforts from international feminist movements support activists and abortion justice movements in Kurdistan?

SAVAN: Solidarity efforts from international feminist movements are extremely important at this stage for activists and researchers in Kurdistan. The lack of resources available in the native language, along with limited opportunities for training and capacity-building, has left many talented young people — who genuinely wish to transform the social landscape of the region — feeling isolated and without proper guidance. International solidarity can provide not only material and educational support but also mentorship, shared strategies, and a sense of belonging that empowers these individuals to channel their energy and commitment into more effective and sustainable actions.

How can people purchase or access the book currently?

SAVAN: The book “91 Days” is a collaborative effort to create an informational resource about abortion. It is a 480-page hardcover book written in Kurdish, aimed at providing knowledge in the mother tongue for the local community.

Currently, the book is available for purchase across the Kurdistan Region through online orders, and it can also be found in bookshop cafés in Sulaymaniyah and Erbil for easier access. For two consecutive years, “91 Days” has also been featured at the Sulaymaniyah Book Fair.

Unfortunately, we have not yet had the opportunity or resources to make it digitally accessible or to translate it into English for broader international reach.